Professors and Instructors Make UofM Happen

Professors and instructors are essential to a university education. While a great portion of their time is spent with students in classrooms and laboratories, ensuring they are successful in their academic paths, much work is done outside the classroom and on personal time. Over the next few months we’ll be highlighting some of that work, as so much of it goes unseen, as well as looking at some of the common misconceptions about these professions.

We’ll be sharing individual profiles on our website and social media channels to help demonstrate the wide variety of responsibilities that these members carry out every day, thereby continuing to make UofM happen.

Profiles

Kathy Block, Instructor, Academic Learning Centre

“We teach both inside and outside the classroom.

What department and faculty/college/school do you work in?

I work as an Instructor with the Academic Learning Centre.

How did you become an Instructor at the UofM? What career path did you follow?

I have a Master’s in Education and a B.A. in Religion and English, and recently completed the Emerging Technologies for Learning Program through Extended Education. I’ve spent most of my career working with adults in academic environments. I started my career as an Instructor with the English Language Centre (ELC) at UofM and then moved into contract work with several different organizations while my kids were young.

Contract work was interesting and creative, most of all, the opportunity to work with the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources (CIER). I worked directly with students in an environmental program on academic reading and writing skills. CIER offered a full-time, two-year program, which was valuable and engaging for the students and a meaningful experience for me as an Instructor. The program was connected to the UofM but taught in CIER’s own space.

In 2001, I went on to work for the University of Winnipeg as the Director of the English Language Program and then came back to the University of Manitoba in 2008.

What does an average week look like for you as an Instructor at the UofM?

My work each week is varied. Mostly, I work with writing tutors. The tutors are students in the upper levels of an undergraduate degree or students working on a graduate degree and are hired and trained to help other students on their written assignments. I work directly with tutors to deliver this program. We’re now tutoring in several libraries and departments across campus. Last year, for example, the writing tutors had 4,500 appointments with undergraduate students.

I also deliver workshops in university classes that are focused on writing, and I meet one-to-one with students. On top of this, I teach a section of Arts 1110: Introduction to University to help students as they make the transition to a new learning environment.

Because of the increasing cost of a university education, many students have to take on a full or part-time job during the year. Do you see the effect of this reality in your classrooms?

Since I’m running a support service for students, I see the effect of students’ busy schedules cutting into the time they have to take advantage of resources. It makes it difficult for students to access programs like the ALC’s Writing Tutor Program because students are on tight schedules. Flexibility in our programming is important.

What are your biggest daily challenges as an Instructor?

It can be a challenge to remain responsive to tutors and students while balancing other responsibilities like delivering workshops and teaching. I like to work with an open door to provide access for students.

What do you think are the most common misconceptions about Instructors on campus? What do you do in addition to teaching?

One of the big picture challenges for Instructors is that we work in many pockets and different areas on campus – it makes it hard to give a blanket statement about misconceptions.

Perhaps a misconception about Instructors is around how teaching is delivered. We consider teaching to include classroom teaching, training workshops, facilitation of one-to-one sessions, and supervision of the students we hire as tutors. It’s all teaching even though it some of it is outside the traditional classroom.

Instructors can also be seen as people who simply deliver programming, but we’re academics too. We’re highly engaged in our academic fields and we need time to reflect, read, write, and assess our work. Like other academics, we need to stand back and look at what’s working and what we need to change.

What projects are you working on right now?

I’m going on a study leave in January 2019. The focus of my leave is to understand the effect of assigning writing tutors to particular courses and how this affects classroom learning, workloads for faculty members, and pedagogy. In partnership with faculty members, we’ve accessed grants to attach tutors to particular undergraduate classes, so this research will be a follow up to that grant money. I’ll be asking questions like, “What can we do better in this initiative?” and looking at faculty perceptions of the writing support.

Why are Instructors important to university life?

Like our faculty colleagues, we are committed to excellence in teaching, learning, and putting students first. We work hard to develop partnerships between our programs and individual faculty members, departments, and faculties. These partnerships are essential to delivering services for students.

Ken Bentley, Instructor and Head Coach, Women's Volleyball

Kinesiology & Recreation Management

“I believe you come to university to find out what’s possible.”

What department and faculty/college/school do you work in?

I am the Head Coach of the Women’s Volleyball with Bison Sports, in Kinesiology and Recreation Management.

How did you become an instructor at the UofM? What career path did you follow?

I started coaching at a young age, right after graduating from high school. Our physical education teacher asked if I’d like to coach the freshman girls’ volleyball team at Murdoch McKay School in Transcona. Volleyball is my favourite sport so I said, “yeah absolutely!” It just happened to be on the girls’ side, and if they would have asked me to coach the freshmen boys’ team I would have jumped at that too. I knew nothing about coaching obviously but knew the sport well enough to give it a go.

A couple of good female friends of mine went on to play at the University of Winnipeg, so I kind of followed them there, and ended up being an assistant coach. I talked my way into a volunteer position there for 4 years which was so instrumental in my career path. Without that experience I wouldn’t be here for sure. In 1986, our men’s coach here at U of M, Garth Pischke, phoned and asked me to come in and talk about a job, which was pretty flattering because Garth is a Canadian icon in volleyball.

What does an average week look like for you as an instructor at the UofM?

An average week in season has evolved tremendously. Here’s a week from late October:

Monday I broke down film from the previous weekend for most of the day before practice, because what I see determines my plan for the upcoming week in competition. Then I trained from 4:00-6:30 and then had a Junior Bison fall camp from 6:30-8:30.

Tuesday I had two individual training sessions during the day with our athletes in between their classes and then we practiced. I finished my planning, took care of some administrative items, and then we practiced from 5:30-8:00.

Wednesday I had one individual training session. Then I was here at the office during the day, then we practiced 3:00-5:30.

On Thursday we left for Calgary to play Mount Royal University. We played Friday and Saturday. Friday morning we practiced at their facility, then we watched film right after that. Then we had the afternoon to study, rest, do whatever the athletes need, and then we played. After the match, I broke the film down for the next morning because we met again to review the film and make whatever adjustments we needed. Then we played again Saturday and flew home late Saturday night. Sunday I was here at 8:30 and I had 2 private lessons with our Junior Bison program between 9:00 and 11:00. Then I had 4 hours of fall camps after that and so I was here from about 8:30 to 3:00 on Sunday. Then Monday it starts all over again.

The Junior Bison program is a huge part of our program. If we’re playing at home, it’s not that different in that we still do our film, we still practice, it’s just that I’m not on the road, but it is pretty much the same pattern/preparation.

What is the typical class size that you teach?

I do some teaching. The varsity team has 14 athletes but it can be anywhere from 12 to 18. I’ve also coached a club team between January and May within our Junior Bison program and that’s another group of about 10-12.

Teaching has evolved as the degree programs have evolved. I used to teach squash, racquetball, volleyball, badminton, and then those activity based courses went away, so now we focus on core sport and coaching expertise. Now I teach advanced coaching theory – the practical component. So students will choose a sport and they get both theory and practical applications in the course. I’m doing the practical component of that course and other coaches team-teach the theory part. That class is usually smaller – between 5 and 10 students.

How have growing class sizes affected your teaching experience?

It’s been the opposite for me personally. Our old activity courses used to have 30-35 students in each quarter.

The demands of our jobs as coaches has grown exponentially over the 32 years I’ve been here, so there’s way more work involved in university sport than there was. It’s just far more professional, the level has increased 10 fold in terms of athlete development coming into university sport, the overall level of university sport, the professionalism of programs across the country, which is all positive, but it leads to increased demands in every area, like generating revenue as a primary example.

Because of the increasing cost of a university education, many students have to take on a full or part-time job during the year. Do you see the effect of this reality in your classrooms?

Behind you is a large cheque for $360,000 that was donated by my great uncle, Davey Einarsson, in 2006. He is an alumni of the U of M, graduating in 1955 with a degree in geological science. He went on to a very successful career in the oil industry. His life story is quite spectacular. I presented a proposal to my great uncle with the goal of creating an endowment fund for our program, and thankfully he supported the proposal. We were able to get that amount matched through the U of M Donor Relations Dept by way of the MSBI Program for a total of $720,000.00. It is by far the most significant event in the history of our program, period. With our student athletes, there is no time to work, because we’re training upwards of 20 hours a week. It’s very rare that an athlete can work while training, on top of their academic load. I think it’s every coach’s goal to provide support to student athletes so they don’t have to worry about that issue. Obviously as costs go up, it’s more stressful for us as we have to find ways to raise more money to support the athletes as we want to, to alleviate the financial stress from them so they can represent the university in the best possible way to put their best foot forward.

What are your biggest daily challenges as an instructor?

Probably in season, getting a day off. I’ve kind of given up on it. I don’t mean that in a bad way, but honestly balance isn’t possible during the season. It’s not realistic. Just trying to carve out meaningful time for your family and for your own recovery is the biggest challenge for sure. Let’s say this weekend as an example, we have a bye-weekend, so we’re not competing, but last night I was watching a high school volleyball tournament for scouting and recruiting, then I will do that again on the weekend, then a full day of Junior Bison camp on Sunday. It’ll be a 6 hour day Sunday likely. Then, it’s 4 full weeks of competing, including travel on weekends, so there’s precious little time for much else. But that’s just the ebb and flow of the season.

Within those times I’ve got to try to find a bit of time for me, to try to keep my energy level strong, so I’ve got to maintain some level of fitness in there somewhere. It’s important for anybody, not just unique to coaching, but my activity level in practice is pretty high if I’m running drills or something, so it’s quite important for me. I would be way more stressed out if I constantly thought about balance, because it’s not possible. So if I use that as my starting point, I just ask where can I make sure I’m carving out the time to make sure I’m connected to my family and trying to maintain some sense of health in my relationships.

What do you think are the most common misconceptions about instructors on campus?

I think that they contribute far more than they’re ever given credit for, especially in teaching workload. It’s challenging because when you’re not in the professorial rank, you’re limited in terms of your advancement. But it certainly doesn’t mean you’re less dedicated or less an expert in your field.

What makes your role unique?

When we are in season, every weekend we compete, for almost 6 months, we write a pass/fail exam as a team. Either you win or you lose every weekend and then you have to absorb what you’ve learned in both cases, and then try the next weekend to be better in what you’re doing. Along the way you’re getting local, provincial, national scrutiny on how your team performs so the kind of visceral environment attached to that weekend upon weekend competition is what I think makes it unique. And no doubt there is a high degree of stress in that we are in the toughest conference in the country (Canada West), and every weekend presents a difficult opponent. We can play well and lose, and certainly if we don’t play well we are going to lose. But that is also the challenge and the excitement of what we do.

Obviously, everyone in the program, in Bison sport, is so heavily invested in what they’re doing. The highs and the lows of each weekend I think is what makes our job unique. Everyone in Bison Sport feels the sting of a weekend gone poorly while feeling elated and excited about a weekend that has gone well too. I’d say that about the whole department from our leadership down. They all play a role in the execution of our programming and they all want it to be better and I would also say we, Bison sport as a unit, is operating at a really high level of commitment and dedication to putting our best foot forward and that’s been really positive.

What’s the best part of your job?

Probably seeing a group reach its full potential. And I mean, that could take a full generation of a team; 4-5 years before that happens. When it does happen, it’s a pretty special feeling because you’ve all committed to this path, made it a priority, and sacrificed a lot of things to make that happen. Ultimately winning a national championship is a part of it, but it’s not the only part. You don’t have to win necessarily to achieve that feeling, but obviously that’s what we’re all shooting for. It’s a pretty special feeling when you have a goal, commit to it, doggedly pursue it – it’s a powerful emotion when you do succeed.

The most powerful part is the self-belief that it creates in a student athlete and that is paid forward for a lifetime. They go on and become leaders in their own right. They amplify that message out in the community in terms of being committed to a goal and seeing it through and having a little bit of persistence, knowing it’s ok to fail and it doesn’t mean the journey is over, just that you learn something along the way. To not give up but to continue to stay on the path. I think that’s just the most valuable piece of this whole thing.

What projects are you working on right now?

Our Junior Bison program has grown tremendously over the last decade, but that’s been my biggest focus outside the Varsity program. Creating year-round programming for the recreational and high performance aspirations for girls’ volleyball between 8 and 18 years old. We’re essentially offering programs year round for volleyball, so we start with mini volley. We have private lessons that go throughout the year, we have high performance summer camps for 2 weeks straight in August. We have fall camps that take place in October/November with private lessons. And then the biggest piece would be our club program which takes place between January and May. This year, we’re going to have a total of 14 teams between 13 years old and 18 years old.

Why are instructors important to university life?

Their value as teachers and what that contributes to the university is really important. I believe that this is the central role of the university. As coaches, I would say, to me, high performance sport really equates to excellence in teaching. My personal feeling is that when you’re trying to compete at the national level, you’re trying to be among the nation’s best. The commitment, the dedication to these goals run parallel to academic excellence and it elicits a high standard.

Not everyone is going to get a Ph.D., but that doesn’t mean someone can’t get a university degree and benefit from it. Many of our athletes and some of our coaches have gone onto some of the highest levels internationally, the Olympics, World Championships, etc. Garth Pischke played in two Olympics which is unbelievable, and we’ve also had alumni play or coach at the Olympic level on both the Men’s and the Women’s side. So I think these are all pretty inspirational, powerful examples of really what is possible. I believe you come to university to find out what’s possible.

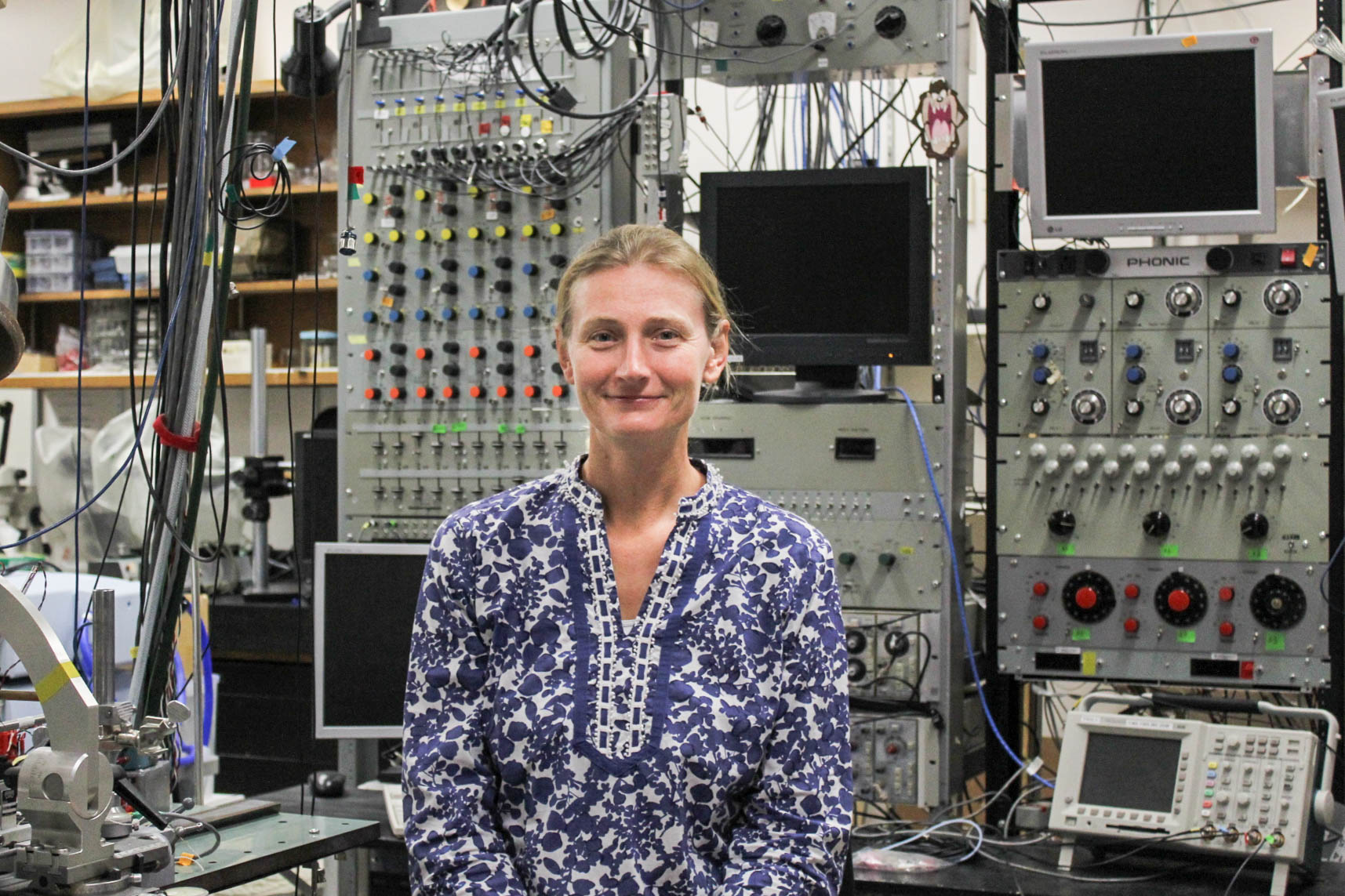

Katinka Stecina, Assistant Professor

Physiology & Pathophysiology

“I came for a visit to see how spinal cord research is done in the labs – and I loved it immediately.”

What department and faculty/school/college do you work in?

I’m in the Physiology & Pathophysiology Department in the Spinal Cord Research Centre (SCRC).

What are some of the projects, research, or publications you’re working on right now?

We are one of the few labs in the world succeeding with applying designer receptors into spinal neurons. I am very excited about this project and I hope to get our publications out to the scientific community and gain valuable feedback soon.

How did you become a professor at the UofM? What career path did you follow?

I was an NCAA Division I Athlete basketball player in North Carolina, USA. My Honour’s Biology professor got me interested in neuro science and encouraged me to go to grad school. He put me in touch with the SCRC in Winnipeg and I came for a visit to see how spinal cord research is done in the labs – and I loved it immediately.

During my Master’s program, I learned more about doing research and I was able to get scholarships to continue my studies. I did my PhD at the University of Manitoba in physiology, with a specialization in life sciences. My research was focused on spinal cord and neuroscience and how spinal neurons integrate and work with each other to organize walking. The purpose of my research is to find better strategies for people recovering from injuries like stroke or spinal cord injury.

What are your biggest daily challenges as a professor?

It can be hard to balance long hours in the lab with my responsibilities for my family and children. It’s always tricky trying to fit everything in, from homework to their after-school work activities and all other “family things” and at the same time, keep publishing results from the lab.

Because of the increasing cost of a university education, many students have to take on a full or part-time job during the year. Do you see the effect of this reality in your classrooms?

Yes, I’ve always noticed this – although, these days it is more like “a must”. This can actually have positive effects too – some of my students who are committed to work in addition to school tend to be much more organized and better prepared than others without the extra responsibilities.

I tell my students to keep their part time job to help them stay on top of things. It’s really difficult to get grants, scholarships, and funding. I’ve noticed - it’s especially bad for international students. I think it’s really important that the Naylor Report suggestions are taken for the sake of grad student training.

A new summer student recently told me that she made more money waiting tables than going to grad school – it’s hard to make that sacrifice and choose further studies when the funding isn’t there to support students. We need to make it more secure, accessible, and attractive to continue to do research.

What makes your role unique in your department or faculty?

Each lab in our Department is a unique “island” of its own. This is because our research varies so widely. Yet, we depend on each other for collegial support and feedback as well as for sharing resources efficiently. So, I do not really consider myself more unique in our Department than any of the other labs.

Many people assume professors take the summer off, is this true?

I wish it was true! The dynamics of our work changes in the summer, and I always try to commit more balanced time for “family” and “work” programs, while in the winter the work programs take up the majority of my time.

What’s the best part of your job?

The interactions with students, colleagues, and such a wide range of people in all areas: location, knowledge base, interest, cultural backgrounds etc. I love learning from others and discovering more about the “details” – little things in life that can help us to be more considerate, efficient, and aware of how we perform different tasks, our research, and teaching.

I also love being able to test an idea using the right tools. Asking questions like, “Can we develop another treatment method?” or “Can we develop another, better way of testing things with human subjects?” I see a whole world of opportunity to use the equipment we have access to and try new things.

Are you involved with communities outside of the UofM as part of your academic work? If yes, why is public engagement important?

I am an active volunteer at my children’s school, coaching sports, and participating in outreach programs through the university. I do outreach with the neuro science network in Manitoba. For example, I help with the high school neuro science competitions. These engagements are important so that our society will be open to working with each other and learn how to better help each other in daily life.

Derek Krepski, Assistant Professor

Mathematics

“I’m always looking for patterns within a defect of a pattern.”

What department and faculty/school/college do you work in?

I work in the Department of Mathematics in the Faculty of Science.

What are some of the projects you’re working on right now?

I’m currently focused on research in an area of geometry or algebra that some people call higher structure, or higher categories. The “higher” here means more hidden. Mathematics is all about structure and trying to understand rules and patterns. Occasionally, you come across something that you thought followed a certain pattern and you have to discover how far off it is from the pattern you thought it was going to follow. I’m always looking for patterns within a defect of a pattern. This theme is something I’m gravitating towards in a couple of projects I’m working on right now. It’s all about adjusting perspectives in order to move forward.

How did you become a professor at the UofM? What career path did you follow?

I got my PhD at the University of Toronto and from there I did two post-doctoral fellowships, one at McMaster University and the other at Western University – I left halfway through that second post-doc because I was offered a job at the UofM.

My area of study and research has been in geometry – more specifically, symplectic differential geometry which is a mix of algebra and calculus.

What does an average week look like for you as a professor at the UofM?

I don’t really have an average week. Each term feels different. During the fall and winter terms, I’m focused more on teaching. I usually teach one large service course (like first year calculus) which can be very time intensive because of how many students are in each class, usually upwards of 100. I spend a lot of time helping students over email. The rest of my week is usually filled with meetings for committees, and any time I have left over is used for research.

What are your biggest daily challenges as a professor?

I feel lucky that I get to do something I’m passionate about every day and things are generally positive. My biggest challenge is managing time. I feel like I’m half teacher and half researcher. Sometimes the two mix, which is great. But sometimes they don’t. I don’t want to say no to students or meetings, but a challenge to then fit in research.

Because of the increasing cost of a university education, many students have to take on a full or part-time job during the year. Do you see the effect of this reality in your classrooms?

Yes, definitely. On the one hand – it can be an issue if students can’t make lectures because of work commitments. I really want students to come to class and participate, ask questions, and get the most out of their educational experience. On the other hand, I understand if a student needs a job in order to get an educational experience in the first place. It’s unfortunate that this can have negative impacts on their learning experiences.

Are you involved with communities outside of the UofM as part of your academic work? If yes, why is public engagement important?

My research is theoretical in nature – there’s not always a particular application in mind. Although I’m studying these theories and concepts for their own sake, someone could always pick up one of these ideas and find a way for it to benefit humanity directly sometime in the future.

I think it’s generally important for everyone in the department, and mathematicians in particular, to take opportunities and show people that math is great and it’s not scary. Sometimes I get to do a guest lecture, or run math contests to get kids in K-12 system excited about doing math. Math can be fun, as corny as it sounds.

What do you think are the most common misconceptions about professors on campus?

When I say I’m a mathematician, I tend to hear a lot about people’s insecurities related to math. There seems to be a prevalent and common distaste for math. I try to communicate that mathematics can be creative as you’re trying to work through thoughts and ideas in order to place them in a certain framework. But it can be hard to describe exactly what my research in geometry looks like since it’s more on the theoretical side, done through reading, pen, and paper, and writing things out on a whiteboard.

What’s the best part of your job?

The best part of my job is that I get to keep learning. In a broad sense, I continue to do that same things and teach similar topics, but because of the research element, I get to live the student experience forever. I’m always looking in textbooks and journals and discovering new research and other people’s unique ideas. I love that I get to maintain an attitude of lifelong learning. It’s exactly the experience I want my kids to have – to be lifelong learners.

In some definition of the phrase, I’m “making it” as a mathematician, but that doesn’t mean I still don’t find it hard. I read papers or textbooks and I’m always trying to learn something new but it still feels difficult at times. Sometimes it’s frustrating but it’s also so satisfying when an idea or concept finally clicks. I love that my job allows me to experience that feeling.

Emily McKinnon, Instructor

Access and Aboriginal Focus Programs

What department and faculty/college/school do you work in?

I work in the Division of Extended Education, in the Access and Aboriginal Focus Programs.

What projects are you working on right now?

I’m focused on increasing the success of Access students in science and math at the university level. Our program has ~180 students, representing students in many faculties and degree programs. About 85% of our students are Indigenous, the rest are newcomers, northern residents, and low-income students. One of the unique and most beneficial things the Access Program offers is that we teach our own first year courses. For example, I teach first year biology in a special, small section, offered only to our students – the regular sections of the same course have over 200 students per class and my classes are usually less than 20. I am also responsible for supporting our students in math and other science courses, by organizing tutors (free for Access students), study sessions, extra workshops, and connecting them with resources on campus.

How did you become an instructor at the UofM? What career path did you follow?

I studied migratory songbird ecology during my PhD at York University and continued that research in my post-doctoral fellowship at University of Windsor. I taught courses as a sessional instructor in biology at the University of Winnipeg and University of Manitoba during my postdoc.

My role with the Access program is my first move to a position focussed primarily on teaching. The Access program is designed to support students facing barriers and help them succeed in academia. I work closely with personal counselors, Indigenous elders, and academic advisors to give students holistic support throughout their university experience.

What does an average week look like for you as an instructor at the UofM?

I spend most of my time teaching and working directly with students. Access Program is located at Migizii Agamik so I get the chance to attend ceremonies with our grandfather-in-residence Wanbdi Wakita, and other cultural events, and learn about various ways to support our students in a culturally sensitive way. I also run workshops every week to give our students extra learning opportunities related math and science courses.

Because of the increasing cost of a university education, many students have to take on a full or part-time job during the year. Do you see the effect of this reality in your classrooms?

Most of our students get student aid or band funding. But this is usually just a drop in the bucket. Many of them still need to get jobs to support themselves and often their dependants. By the time they get to their second year, it’s almost a guarantee that they have to work as well as attend classes.

The provincial government just recently cut all of the Access bursaries (some students in Access previously got a non-repayable bursary to top up their student loans; for the first time, this is no longer available to our students). If you have to get a job as well as keep up with school work, then you’re distracted from studying and it inevitably impacts your grades. It makes it harder for students to get into highly competitive professional degree programs like medicine. It means we aren’t feeding these students into the pipeline for professional health careers and the end result is a diversity and inclusivity problem.

If students aren’t taking advantage of all opportunities available, it’s because they’re working, paying for daycare, or helping care for extended family.

What do you think are the most common misconceptions about instructors on campus? What do you do in addition to teaching?

People assume I do research. And people always think I have summers off. I’m actually really busy in the summer. I run summer camps for northern students during the summer, a math prep camp for Indigenous students, and we do extensive orientation for incoming Access Program students. In the Access program we also interview every new student we take into the program. There’s always lots going on!

What makes your role unique?

There aren’t a lot of full-time instructors in Extended Ed compared to a traditional faculty like Science or Arts. Furthermore, in Access, instructors have a really unique role because of the holistic way we approach things. We work as a team to provide a strong emotional, spiritual, physical, and academic supports for our students. It’s really a model system that would benefit so many students.

Why are instructors important to university life?

We’re teachers that interact with students on a daily basis. We allow professors to focus on their research while we provide the backbone by teaching many intro and core courses. In first year especially, this is where we can help students get on their feet. We want to set them up well for their whole degree, so they can excel in upper year courses, and work on their own research with professors in their senior years. They wouldn’t make it to the honours level without the great instructors teaching them along the way!